Experimental: Protecting Deep Learning Model through Range Supervision (“Ranger”)¶

Introdution¶

Deep neural network find applications in many scenarios where the prediction is a critical component for safety-relevant decisions. Such workloads can benefit from additional protection against underlying errors. For example, memory bit flips (**”soft errors”** originating, e.g., from external radiation or internal electrical disturbances within the circuitry) in der platform hosting the network inference can corrupt the learned network parameters and lead to incorrect predictions. Typically, errors resulting in very large parameter values have a more drastic impact on the network behavior. The range supervision algorithm (“Ranger”) described here establishes and inserts additional protection layers after already present activation layers. Those layers truncate values that are found to be out of an expected activation range in order to mitigate the traces of potential platform errors. They do so during inference by applying a clamp operation to any activation x in the input to the Ranger layer,

x = clamp(x ; T_{low}, T_{up}) = min(max(x, T_{low}), T_{high}))),where $ T_{low} $ and $ T_{up} $ are the lower and upper bounds for the particular protection layer, respectively.

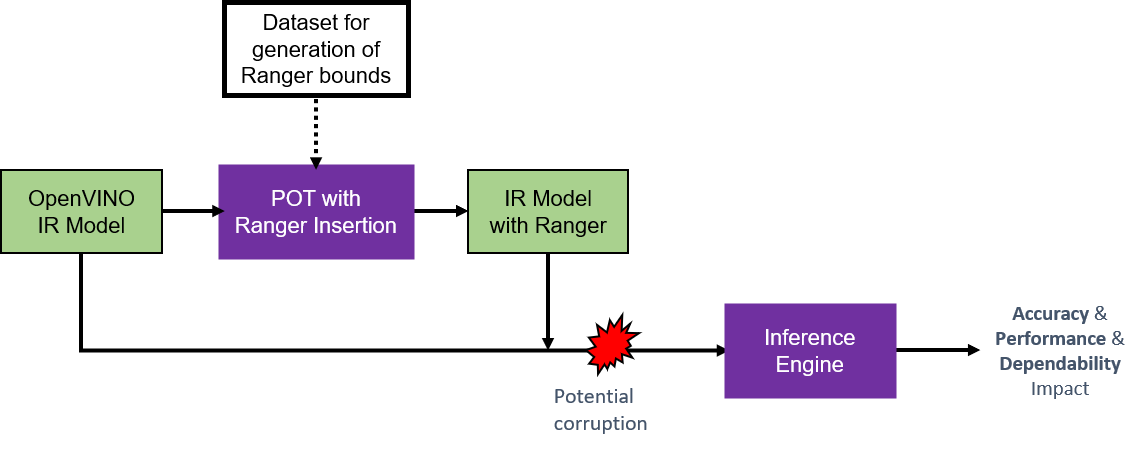

The process flow follows the diagram Fig 1. Starting from the internal representation (IR) of an OpenVINO model, the POT Ranger algorithm is called to add protection layers into the model graph. This step requires appropriate threshold values that are automatically extracted from a specified test dataset. The result is an IR representation of the model with additional “Ranger” layers after each supported activation layer. The original and the modified model can be called in the same way through the OpenVINO inference engine to evaluate the impact on accuracy, performance, and dependability in the presence of potential soft errors (for example using the benchmark_app and accuracy_checker functions). The algorithm is designed to provide efficient protection at negligible performance overhead or accuracy impact in the absence of faults. Bound extraction is a one-time effort and the protected IR model returned by the Ranger algorithm can be used independently from there on. No changes in the learned parameters of the network are needed.

Fig 1: Schematic of Ranger process flow.

Supported activation layers¶

The following activation layers are currently supported for range supervision:

ReLUSwishPReLUEluGeluSigmoidTanh

This means that any activation layer of one of the above types, that the model under consideration contains, will be protected with an appropriate subsequent Ranger layer.

Usage¶

Ranger protection can be used the same way as DefaultQuantization method.

Algorithm configuration¶

Algorithm has a minimal configuration. Below is an example of such configuration:

{

"name": "Ranger",

"params": {

"stat_subset_size": 300

}

}The protected model will be saved in IR format in a new folder *./results/<model_name>_Ranger/…* .

Mandatory parameters:

"stat_subset_size": This parameter defines how many images of the specified dataset in “engine: config” are used to extract the bounds (images are randomly chosen if a subset is chosen). This value is set to 300 by default. The more images are selected for the bound generation, the more accurate the estimation of an out-of-bound event will be, at the cost of increasing extraction time.

Example of Ranger results¶

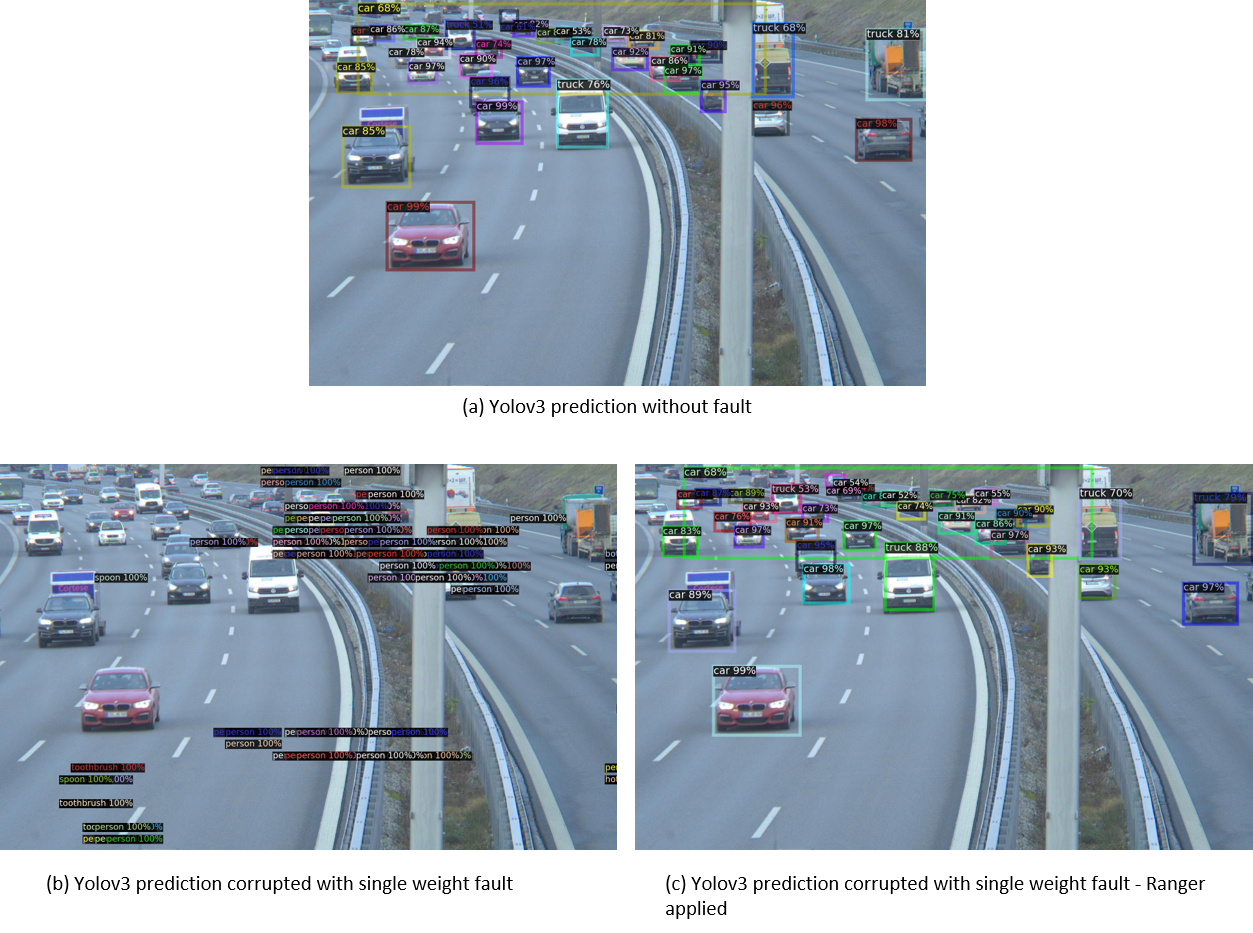

The following example shows a traffic camera image and predicted objects using a Yolov3 pretrained on the Coco dataset. A single weight fault was injected in a randomly chosen convolution layer of Yolo, flipping the most significant bit of the selected network parameter. If range supervision is applied, the original network performance is recovered despite the presence of the fault.

Fig 2: Example of fault mitigation via range supervision.

Resources:¶

Chen, G. Li, and K. Pittabiraman, “A Low-cost Fault Corrector for Deep Neural Networks through Range Restriction”, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.13874

Geissler, Q. Syed, S. Roychowdhury, A. Asgari, Y. Peng, A. Dhamasia, R. Graefe, K. Pattabiraman, and M. Paulitsch, “Towards a Safety Case for Hardware Fault Tolerance in Convolutional Neural Networks Using Activation Range Supervision”, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07019